Diffraction, Or Overcoming My f /11 Entekaphobia

Editors Note: With the rumor mill alive with speculation about a soon to be announced Sony A7R Mark II with a whopping 59MP of resolution, a discussion immediately came up with some of my professional photographer friends about where is the actual diffraction limit going to be with a Sony 59MP full frame sensor? The limit being the point where you stop a lens down any further and you actually degrade the image due to diffraction, not improve the sharpness. I can bear out what Roger’s findings are in his article, though i can not nearly match his elegance in presentation nor the persuasiveness of his arguments. I decided to let Roger tell this story, and I will ask him to update it once this mystery camera actually starts shipping.

What does this header image have to do with diffraction? To prove a point, and to get maximum DoF using a medium format lens, I shot it at F32 testing a new Fotodiox Pro lens adapter! – Chuck Jones

Entekaphobia – fear of the number 11

Or. . . How I Learned to Appreciate Small Aperture Photography

If you read my blog much, you know I’m a resolution fanatic. I test every new lens for resolution. For personal use, I’ll choose the lens with higher resolution over the one with creamy bokeh every time. When choosing a camera, I have a (yes, I’m ashamed to admit it, but it’s true) strong tendency to want the most megapixels. I’m a resoholic.

Being a resoholic, I’ve always been somewhat fanatical about apertures. Whenever possible I shoot with the lens stopped down at least one stop to wring the maximum sharpness out of my lens. But I’m always careful not to stop down too far because I was taught, soon after I picked up a camera, that if you stopped down too far the dreaded diffraction softening would kick in.

With today’s high-pixel density cameras, that meant f/8 was as far as I would ever stop down. My mental map of aperture sharpness was like the ancient maps of the world – past f/8 there was nothing but the notation Here Thar Be Monsters. Or the equivalent label in Latin or Olde English, just because that makes it seem much cooler.

Detail from The Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557).

Go to f/11 and the diffraction monster would come and eat the resolution right out of your photographs. The diffraction monster loves to snack on some tasty resolution. When testing I really never checked past f/5.6 or f/8. That’s where the maximum resolution would be. Any further, and, well, you get it by now.

But I knew there were excellent photographers who shot their landscapes and macros at f/11 or even f/16 because they needed the depth of field. I heard rumors of photographers in far off lands who even actually took photographs at f/22. I considered them sort of like those guys who jump off cliffs in batsuits and fly around for a while before pulling their parachute rip cords. It was fascinating to know people did that, but made me a bit queasy. I was certain the survivors would eventually learn the error of their ways.

But lately, some people like Tim Parkin at Onlandscape.com started opening my eyes (by repeatedly beating on my head). They claimed to be shooting at f/16 and even f/22 with high-pixel-density SLRs, carefully postprocessing their images, and getting very nice detailed results. I shook my head sadly at first, hoping they would come to see the light (pun intended). But then I looked at Tim’s recent article The Diffraction Limit and had to admit, their f/22 images didn’t look bad at all.

So I decided it was time to open the closet door and see just how bad the diffraction monster really was.

Preliminaries

Before we get into all of this, let’s remember we’re looking at two simultaneous events when we stop a lens down. I am not going to get into lengthy discussions of Airy Discs, Raleigh Criteria, and other arguments here. You can read about them elsewhere. This is the simple overview of what’s going on.

- 1) As we narrow the aperture (higher f/number) diffraction occurs which causes some loss of resolution.

- 1a) Smaller pixels are affected more than larger pixels since diffraction causes a spread of the point into a disc. A disc of small size might still fit nicely on a large pixel, but might cover two small pixels. The math is mildly complex, it’s not linear, and I’m not going into it more than that.

- 2) As we narrow the aperture, the lens resolution increases.

- 2a) The increase is different for different lenses.

- 2b) The increase may occur at different rates for the center, middle, and corners of a lens.

- 3) Decreasing aperture is sort of a race between these two effects. When we first stop down, the lens sharpening is greater than the diffraction softening. As we stop down further, lens sharpening slows or stops, but diffraction softening continues.

Some Resolution Testing

I’m not one to really believe what I see in online exampless; given enough postprocessing an online jpg can look pretty sharp if the lens was the bottom of a beer bottle. I want at least a side dish of numbers or some comparative crops with my reviews, thank you.

I decided our current Nikon lineup gave me a great opportunity to look at diffraction effects. By shooting the same lenses on a D700, D3x, and D800 I can look at full-frame sensors with 12, 24.5, and 36 megapixel sensors. That gives linear pixel densities of 118, 168, and 204 pixels per mm, respectively.

I decided to use 50mm lenses because we have 3 choices that are quite different in how they behave at various apertures. The Zeiss 50mm f/1.4 (the schizoid fiftoid) is very soft and dreamy looking wide open, but becomes razor sharp once stopped down to f/5.6 – it’s like two lenses in one. The Zeiss 50mm f/2 Makro planar is quite sharp even wide open, but seems to maximize it’s center resolution by f/4. The Nikon 50mm f/1.4 G is reasonably sharp wide open, but seems to keep getting sharper the more you stop it down.

So I tested all 3 lenses on all 3 bodies at apertures from wide open to completely stopped down in our Imatest lab.

The Effect of Stopping Down on MTF 50

I started right in the middle of my selections: the Nikon D3x with the very predictable Nikon 50mm f/1.4 G lens. Here are the MTF 50 values in line pairs / image height for the center point, weighted average of 13 points, and average of the 4 corner points. Please note that the plotted average is NOT just the average of center and corners, so if the ‘average’ value is near the center, you know the lens stays fairly sharp in the middle regions, while if it’s nearly as low as the corners the lens falls off rapidly away from the center point.

Nikon 50mm f/1.4 on D3x at various apertures

I have to admit I was a bit shocked. Just as expected, the resolution starts to decrease after f/8, but it doesn’t decrease all that much. Even at f/16 the resolution is still quite a bit higher than it was at f/1.4.

The next step was to see how things look with lower and higher pixel density cameras. So I shot the same lens on a D700 and D800.

Nikon 50mm f/1.4 on D700 at various apertures

I was a bit surprised here, too. I had expected the lower pixel density of the D700 would shift the peak resolution a bit, perhaps to f/11, but that wasn’t the case, although the drop after f/8 did seem less severe.

Nikon 50mm f/1.4 on D800 at various apertures

Things weren’t as different as I expected on the D800, either. The center does seem to peak around f/5.6 with the corners peaking at about f/8, which isn’t surprising. The other cameras show only a slight increase in resolution at the center between f/5.6 and f/8 so it makes sense there would be a bit stronger diffraction effect on the D800. I had really expected more than this. The lens still improves in the corners strongly between f/5.6 and f/8 and the improvement is greater than the diffraction softening.

The message I took away, though, is that diffraction softening is real, it occurs where it is supposed to, but it’s really not as severe as I had thought. Even on the D800 resolution is as high, or higher, at f/16 than it was at f/2.8. At f/11 the resolution is as good, or better, than at f/4. And at both f/11 and f/16 resolution is clearly higher than it was wide open. Perhaps the diffraction monster’s teeth aren’t as long and wicked as I thought.

Some Different Lenses

Diffraction softening is fairly constant, but lens sharpening as the aperture decreases is not. Different lenses behave differently. I compared the Zeiss 50mm f/1.4 and 50mm f/2.0 Makro Planar lenses to the Nikon 50mm f/1.4 G we tested above on all three cameras. In the interest of brevity we’ll just show the graphs for the D3x. The variations for the D800 and D700 were similar to these.

ZF 50mm f/1.4 on D3x

ZF 50mm f/2 Makro on D3x

Let’s start with wide open performance. At f/1.4 the ZF f/1.4 lens isn’t as sharp as the Nikon 50mm was, while the ZF 50mm f/2 Makro is sharper at f/2 than either of the other lenses at that aperture. The f/2 Makro has reached maximum center sharpness by f/4 and then slowly loses resolution. The lens doesn’t reach maximum corner sharpness until f/8. The ZF 50mm f/1.4 gets maximum center sharpness at f/5.6 and corners again at f/8 on the D3x. (In the graph above, you can see the Nikon reached maximal sharpness at f/8 for both centers and corners.

The pattern was unchanged on the D800, but on the D700 the two Zeiss lenses center sharpness shifted just a bit to the right – moving to f/5.6 for the 50mm f/2 Makro, with corner sharpness remaining peaked at f/8.

So there is some difference in stopped down behavior with different lenses. Before you ask me to go test this or that, the work has largely been done already at sites like SLRgear.com and Photozone – they show center, corner and edge sharpness at various apertures in their lens reviews.

Yes, I Took Pictures

OK, the numbers surprised me a lot, so I went and did what had to be done. I actually took photographs stopped down to f/16 and even f/22.

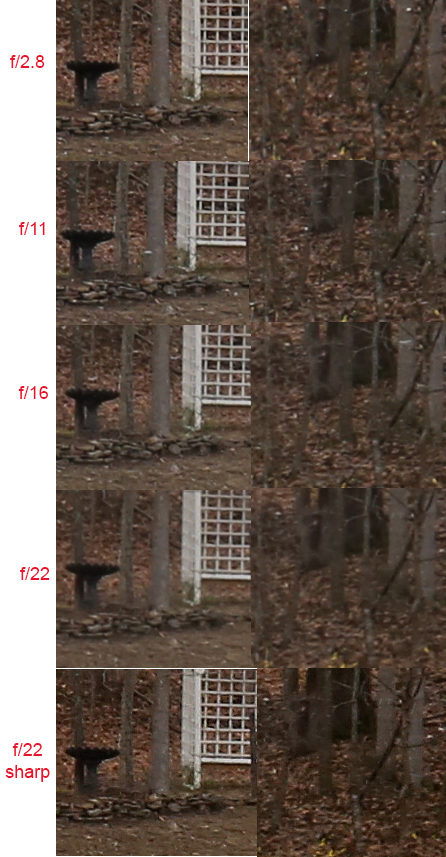

Here’s one picture I shot at various apertures (this was on a Canon 6D).

What I saw mirrored what the numbers said I would see. Below are some 100% crops of the white gazebo just off center and some tree trunks near the left edge. I also tried something I was told was possible, but hadn’t really believed. I took the obviously diffraction softened f/22 image and did my best to sharpen it in Photoshop. (By best, I mean about 45 minutes testing different combinations of sharpness and contrast enhancement in 3 layers before getting the results shown below as ‘f/22 sharpened’.)

I haven’t tried this kind of sharpening before and was feeling my way along. I’m sure it would be better with practice (I blacked out the large tree-trunk for example and the image is about 1/3 stop darker than when I started) but still I found the results surprisingly acceptable.

One thing I found very interesting is that I could perform what was basically postprocess abuse on the f/22 image to a degree that would have been impossible with one of the other shots. Below, for example, is the f/2.8 image above processed with exactly the same settings I used on the f/22 image. The center crop, particularly, looks like a ‘find edges’ special effect filter.

I don’t mean to suggest that the postprocessed f/22 image is going to be as good as a nice f/5.6 or f/8 image at all. Rather I’m suggesting it can be improved to a larger degree than they can, making up some of the out-of-camera difference between them.

Does this mean f/16 is my new f/5.6? No, not at all. But I think I may become a lot more aggressive about using f/8 and f/11 when I’m trying for a larger depth of field. I even might use f/16 if absolutely needed. I don’t think I’ll be shooting f/22, though. That’s just a step too far for me.

Roger Cicala

Please rate this story, and why not share it with your friends? [ratings]